Jefferson Gary and the Quiet Power of Invention

A Self-Taught Mind at the Turn of the Century

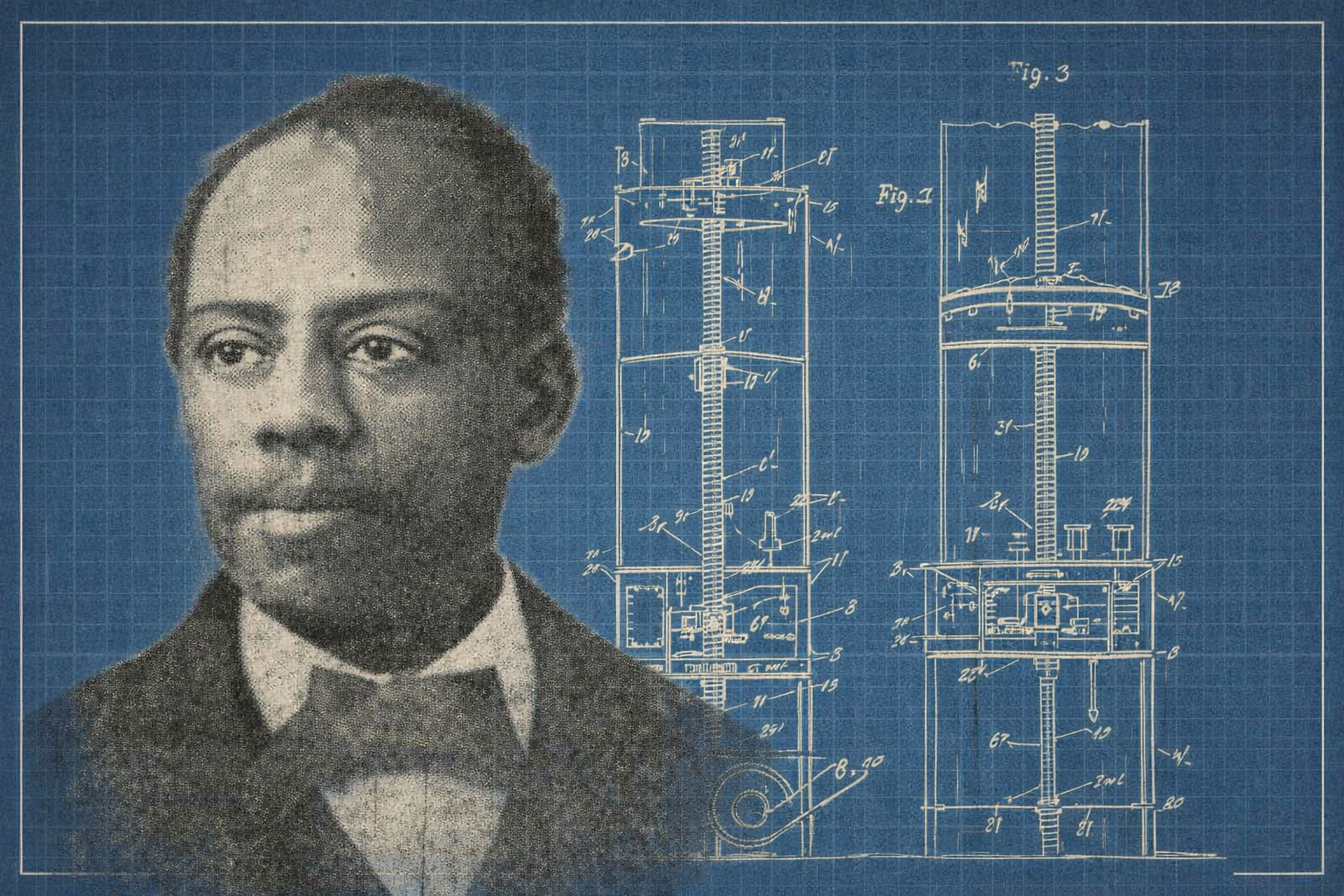

In August 1900, Jefferson Gary submitted plans to the U.S. Patent Office for an elevator that defied convention. His design eliminated cables, counterweights, and pulleys—components so fundamental that few engineers thought beyond them. Gary did.

He was not trained as a mechanic. He was not employed by a firm or backed by a university. He worked with pencil and paper in his St. Louis home, returning night after night to a problem sparked by a single conversation overheard while working for a West End family. An elevator had fallen in a downtown building. For six years, Gary pursued a safer alternative.

When the patent was granted and arrived in November 1900, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat took notice. Reporters described a man of slight build with strikingly alert eyes—eyes that hinted at “perception and mental grasp.” Born in Eufaula, Alabama, Gary had come to St. Louis a decade earlier and supported himself through labor and domestic work. Innovation, he said, came not from schooling but persistence.

The elevator was only the beginning.

Between 1900 and 1903, Gary patented multiple vapor-burning stoves and a rotary engine—each focused on efficiency, durability, and simplicity. These were not idle sketches. They were complete, examinable systems that passed federal scrutiny. In the language of the Patent Office, they were new.

Why It Matters

Jefferson Gary’s story reminds us that creativity is not measured by commercial success.

At the turn of the twentieth century, thousands of Americans—especially self-taught inventors and working-class thinkers—generated ideas that advanced engineering without ever reaping reward or recognition. The patent itself was often the finish line, not the starting gun.

Gary’s life challenges our modern instinct to ask, “Did it sell?”

A better historical question might be, “Did it expand what was thinkable?”

By that standard, Gary succeeded.

His elevator challenged dominant assumptions. His stoves reimagined fuel efficiency. His rotary engine pursued compact power long before such concepts became mainstream. That these ideas may not have been manufactured does not diminish them—it situates them within the real constraints of capital, and access in early 20th Century America.