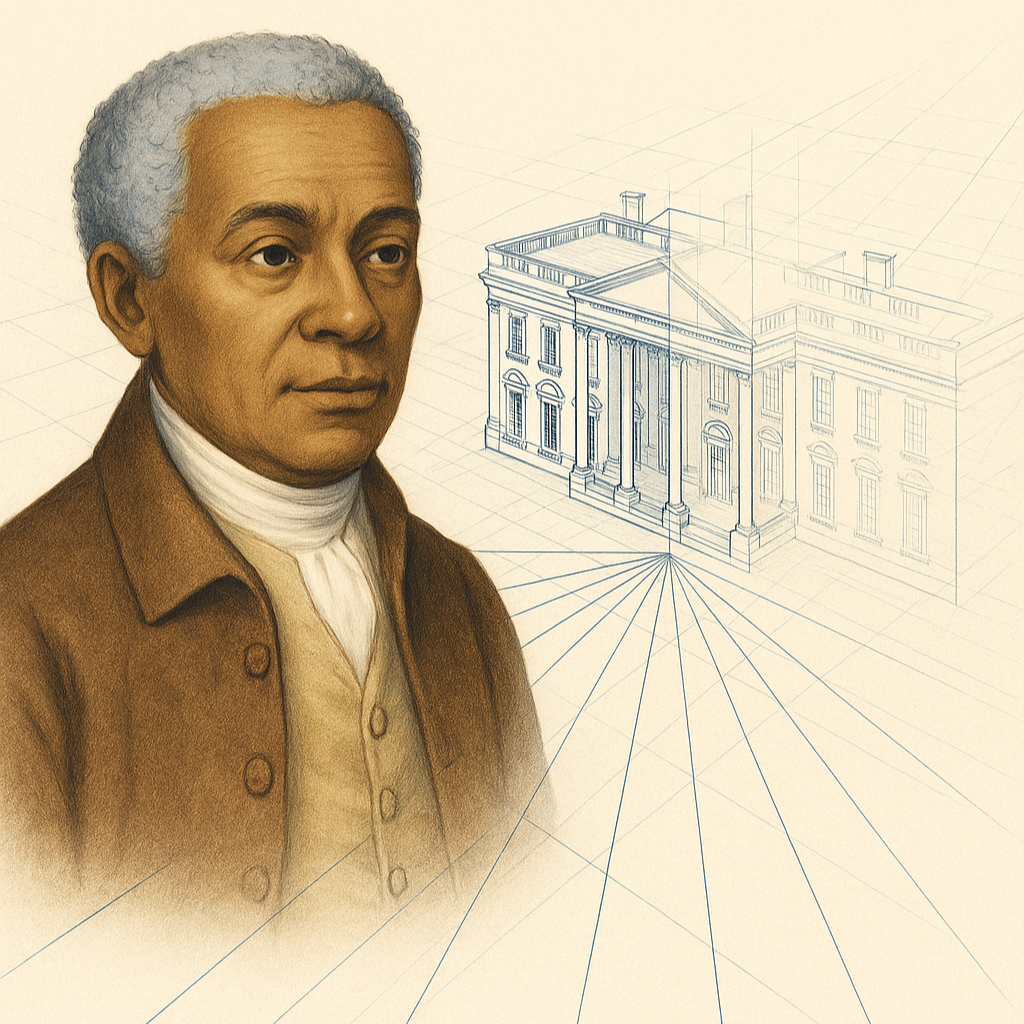

Benjamin Banneker and the New Capital

“This calculation is the production of my arduous study, in this my advanced stage of life… having long had unbounded desires to become acquainted with the secrets of nature.”

—Benjamin Banneker to Thomas Jefferson, August 19, 1791

These words, composed in a letter that sixty-year-old Benjamin Banneker wrote to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson on August 19, 1791, accompanied a manuscript of Banneker’s first almanac (he would produce at least ten more, up until 1802). Banneker explained that he had almost decided against undertaking this project “in consequence of that time which I had allotted therefor, being taken up at the Federal Territory, by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott.”

Jefferson instantly understood the reference to the “Federal Territory.” He had, after all, been instrumental in ensuring that the nation’s capital moved permanently to the Potomac by organizing the dinner with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in June 1790. He had also personally submitted Banneker’s name to President George Washington, recommending him as a member of the commission created to define the boundary lines and lay out the street grid for the District of Columbia. Ellicott had likely suggested Banneker for service on the commission, for he had first-hand knowledge of his friend’s proficiency in mathematics and surveying, skills essential to constructing the new federal city.

Banneker soon began work with Ellicott and Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French engineer, on putting their rather ambitious plans in motion: boundary lines measured, angles calculated, streets aligned to compass points and celestial observation.

Though his tenure on the project was brief, Banneker’s contribution was foundational. The new capital was not merely placed on the Potomac—it was mathematically anchored, surveyed, and rendered navigable in part through his labor.

Why It Matters

Thomas Jefferson helped determine where the nation’s capital would be built.

Benjamin Banneker helped determine what it would look like—and how generations of Americans would move through its streets and neighborhoods.

His presence in the founding of Washington, DC, reminds us that the early republic depended not only on political compromise, but on scientific knowledge, intellectual rigor, and contributions too often left out of the story.

Sources

Woody Holton, Black Americans in the Revolutionary Era: A Brief History with Documents (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2009), 108–111.

John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, 7th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 94–97.