From Mockery to Marketing: How “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” Changed Campaigns Forever

They looked like harmless pieces of sheet music — playful “comic glees” printed for conventions in Syracuse and Boston. But in 1840, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” was no parlor song. It was part of a sophisticated Whig effort to turn Democratic ridicule back on its creators.

Democrats had mocked Whig candidate William Henry Harrison as an old soldier, past his prime, who only wanted to sit in his log cabin and drink hard cider. The Whigs didn’t run from the insult — they appropriated it and turned it into a symbol of popular appeal. “Tippecanoe Clubs” sprang up across the country, celebrating the very imagery meant to belittle Harrison, and pairing him with his running mate, John Tyler of Virginia.

The Attack — and the Backfire

The Democratic press wanted voters to see Harrison as too old, too rural, and they mocked his presidential candidacy as a vehicle for him to secure a federal pension that would allow him to retire to a log cabin where he could spend his final days guzzling hard cider. But once the Whigs embraced the log cabin, the Democrats’ own imagery started to work against them.

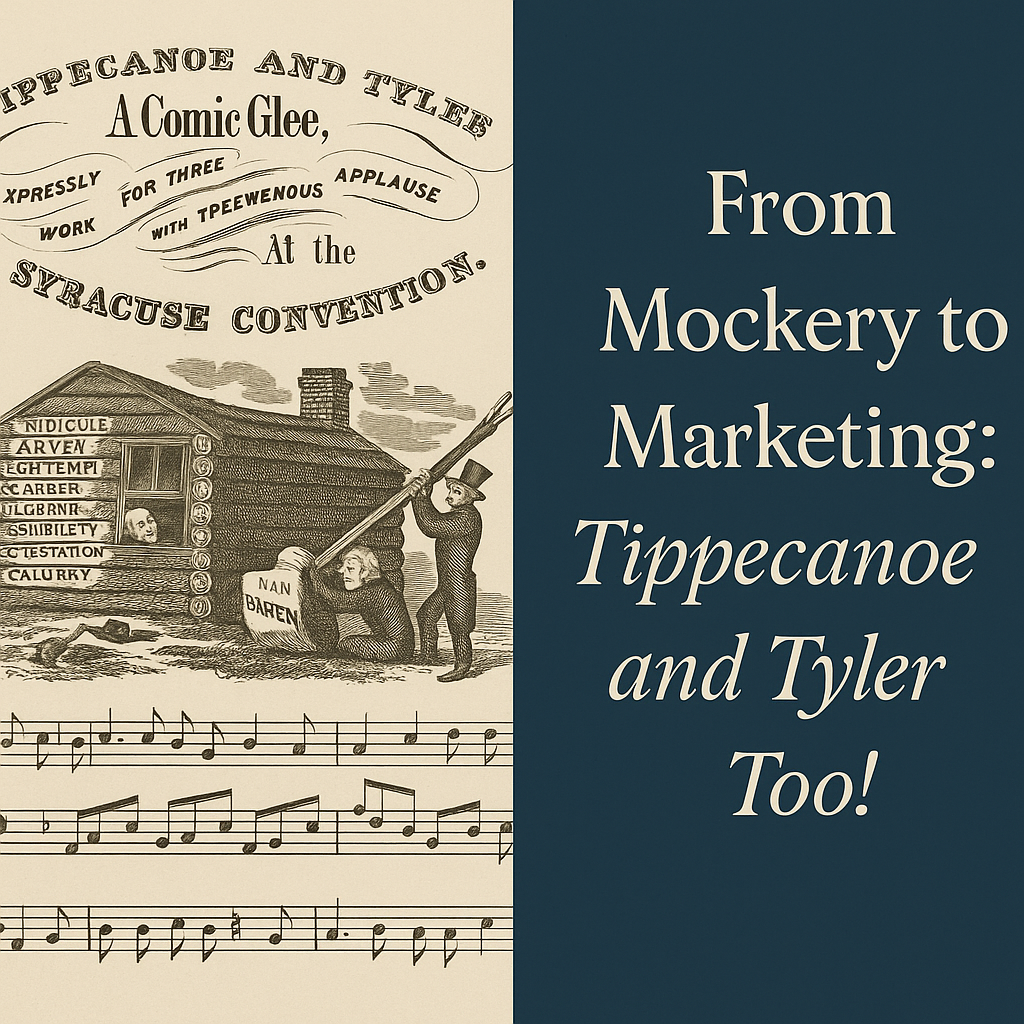

That’s what makes the G. E. Blake sheet so clever. In the illustration, Van Buren himself is shown inside the log cabin — the very symbol Democrats tried to stick on Harrison. Outside, an elderly gentleman with a hickory pole — a clear nod to Andrew Jackson and his hickory symbolism — is straining to pry him out. But the caption makes the point: “The logs are too heavy and growing more so daily.” In other words, Van Buren is trapped by his own party’s political gambit. The Whig message is, “You tried to make the 1840 race about log cabins — now you’re the one stuck in it.”

So this sheet isn’t anti-Harrison — it’s anti–Van Buren, delighting in the way Whig imagery has boxed him in.

The Counterpunch: The Whigs Turn the Joke

Once they saw the opening, the Whigs ran with it. As Christopher J. Leahy observes, the party “had learned a lot about how to wage an effective campaign from the Democrats and intended to beat them at their own game.” (President Without a Party, 2020).

Whig strategists didn’t just answer their opponents — they outproduced them, flooding the public with songs, parades, banners, and imagery that celebrated the log cabin and the cider jug.

As historian Richard J. Ellis explains on page 213, in Old Tip vs. The Sly Fox: The 1840 Election and the Making of a Partisan Nation (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020), “If the candidates were the campaign’s central symbols, their images were constructed by the cartoonists and wordsmiths in the partisan press and by the parties’ veritable army of political speakers who fanned out across the country to spread the party gospel.”

Even some Whig leaders understood that the campaign’s spectacle stretched the truth. Ellis notes on page 218 that Senator Henry Clay and others “had convinced themselves that if Van Buren were re-elected, ‘the Government will be ruined,’ and so reconciled themselves to the ‘hoopla and outright lies about log cabins and presidential palaces.’”

The Whigs may have winced at their own exaggerations, but they knew the stakes — and that vivid imagery could move hearts and votes in ways policy speeches could not.

The second piece, Tip and Ty: A New Comic Whig Glee, dedicated to the Louisiana Whig Delegation, put the whole thing to music:

“O what has caused this great commotion, motion, motion…

It is the ball that’s rolling on,

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too!”

That “rolling ball” became one of the first recognizable campaign memes — a traveling, singable, repeatable image.

Harrison, Tyler, and the Crafted “Common Man”

Of course, Harrison wasn’t actually a poor westerner; he was from a well-off Virginia family and was comfortable by 19th-century standards. But the Whigs in 1840 had a modern sense of how image beats biography. And because Tyler’s name was welded to the slogan — “and Tyler too” — he benefited from the same popular brand, only months before he became president upon Harrison’s death.

Why It Matters

What we see in these two sheets is political jujitsu. Democrats tried to belittle Harrison; the Whigs seized the imagery, multiplied it, and then used it to portray Van Buren — and even Jackson’s lingering influence — as stuck, overmatched, and unable to counter the enthusiasm of 1840.

Mockery became marketing. Satire became strategy. And American campaign culture has followed that pattern ever since.

Image Captions

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too: A Comic Glee. Philadelphia: G. E. Blake, 1840. Whig campaign piece showing Martin Van Buren trapped inside the “log cabin” imagery he had helped unleash, with Andrew Jackson attempting to free him. Library of Congress, Music Division.

Tip and Ty: A New Comic Whig Glee, dedicated to the Louisiana Whig Delegation, 1840. A musical celebration of the Harrison–Tyler ticket. Library of Congress, Music Division.

Further Reading

Christopher J. Leahy. President Without a Party: The Life of John Tyler.

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020.Richard J. Ellis. Old Tip vs. The Sly Fox: The 1840 Election and the Making of a Partisan Nation.

Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2020.

Categories: Early Republic Politics, Campaign Culture, John Tyler

Tags: #TippecanoeAndTylerToo #1840Election #WhigParty #MartinVanBuren #JohnTyler #PoliticalHistory #HistoryInTwoVoices

This post is for educational and historical purposes only. History in Two Voices does not endorse any political party or viewpoint. We share stories from America’s past to foster understanding, dialogue, and appreciation for our shared history.on