Speaking Directly to the Voters

In an era before radio and television—let alone social media—early 19th-century politicians used newspapers to convey their messages to as many voters as possible.

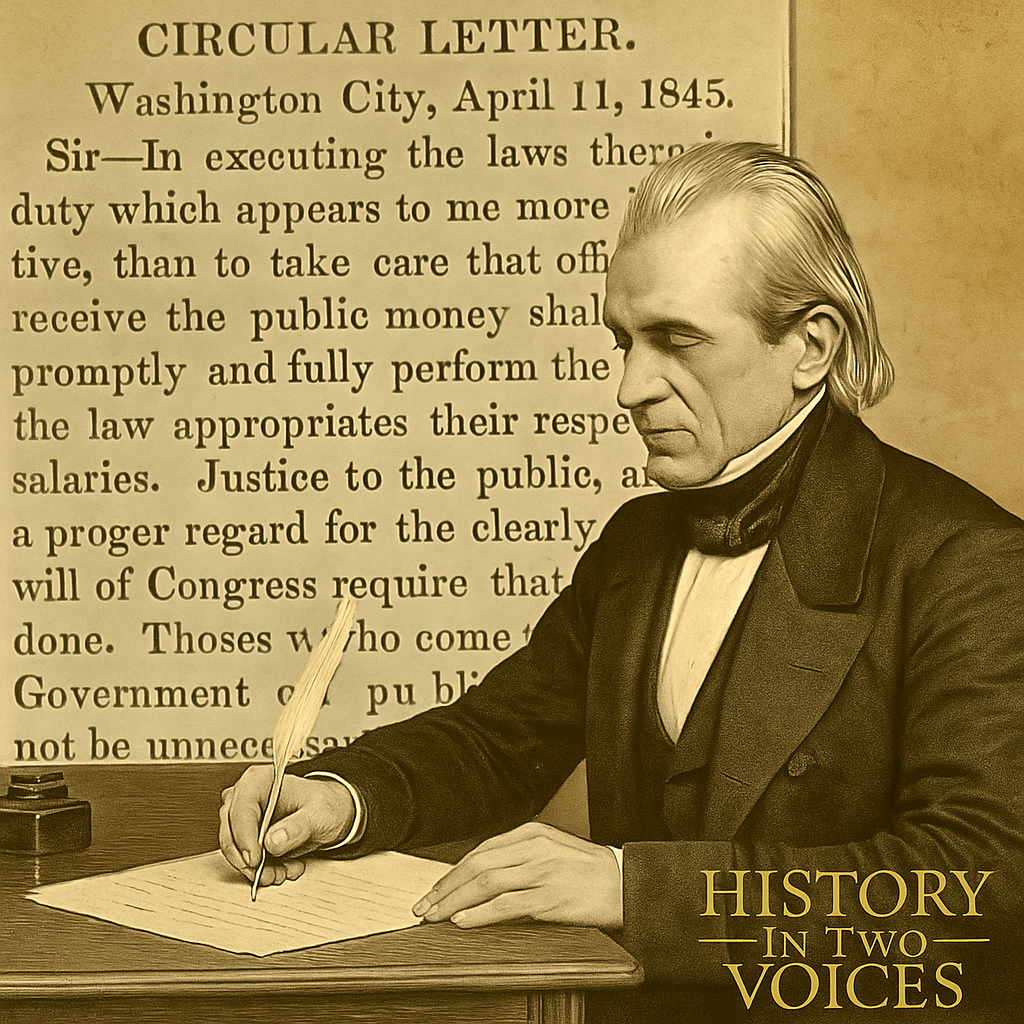

One custom with a long history, especially among southern congressmen, was the publication of circular letters. A circular letter was a report that a member of Congress addressed to his constituents, summarizing his speeches and voting record during the most recent session. A friendly newspaper would then publish the letter in its entirety.

The practice was more common among members of the House of Representatives than senators, for the simple reason that House members were elected directly by the voters in their districts, while senators were elected by the state legislatures. (That changed in 1913, when ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment allowed the people to elect their U.S. senators directly.)

A prudent congressman crafted his circular letters carefully. He had to balance a humble, republican desire to continue serving his constituents in Washington with the need to demonstrate accountability to their wishes—all without appearing to campaign overtly for votes. As John Tyler once put it, he did not want his circular letters to read as a “low, groveling, mean pursuit of popular favor.” Yet he also recognized the importance of showing that he remained answerable to the will of the people.

Why It Matters

Circular letters are an often-overlooked primary source for understanding the evolving relationship between members of Congress and their constituents in the early national period of U.S. history. Reading them closely yields valuable insights into the development of American politics—from the deferential structures of the late 18th century to the more “democratic” ethos of universal white manhood suffrage that defined what some historians still refer to as the “Age of Andrew Jackson.”

Further Reading

Christopher J. Leahy, President Without a Party: The Life of John Tyler (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020), p. 45.

Images:

Composite image featuring James K. Polk writing at his desk and excerpt from his “Circular Letter,” originally published in the Spirit of the Age (Woodstock, Vermont), May 15, 1845. Digital composition created by History in Two Voices, 2025.

This post shares an educational story from early U.S. political history and is not related to current politics or elections.