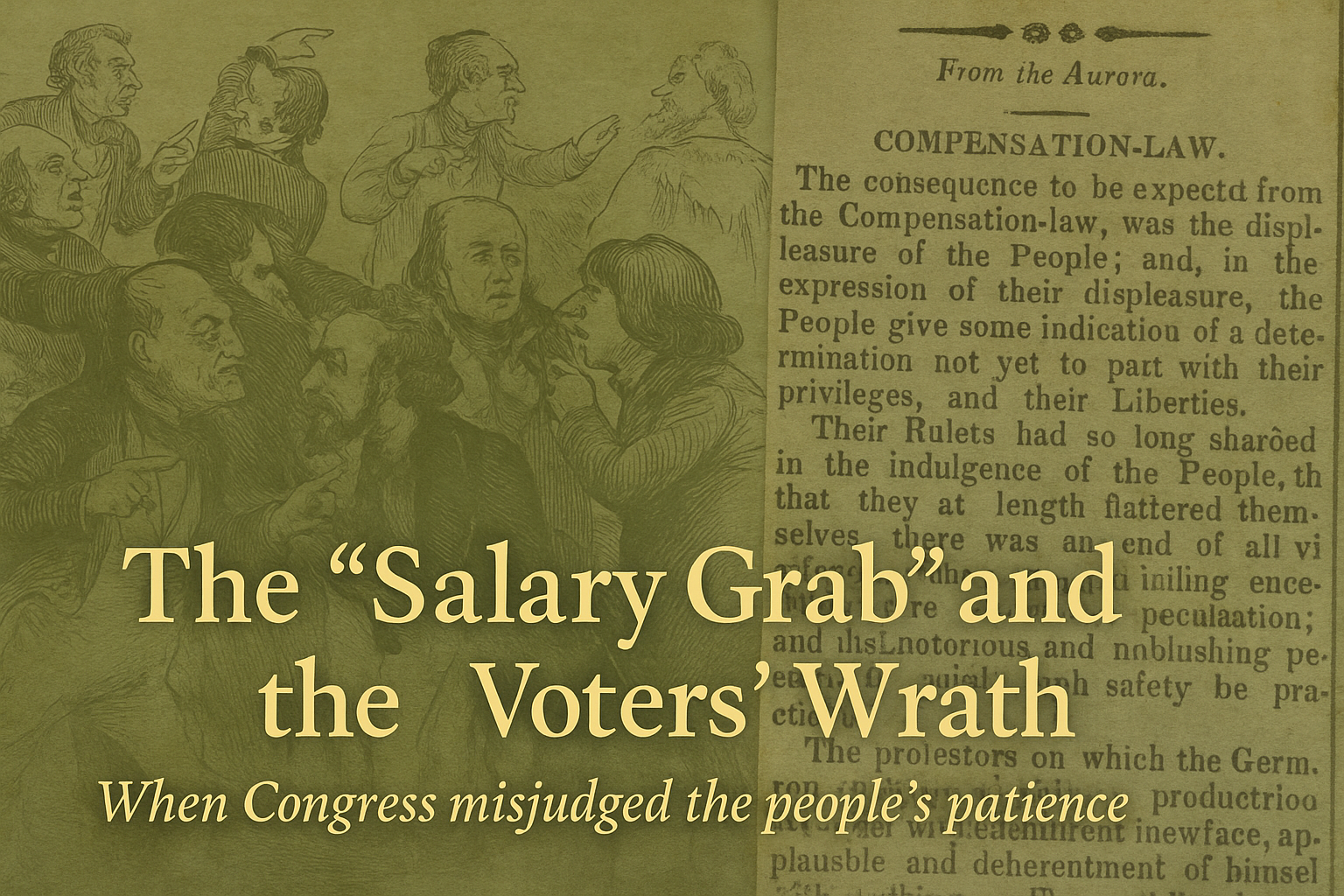

The “Salary Grab” and the Voters’ Wrath

In March 1816, Congress passed—and President James Madison signed into law—a bill called the Compensation Act, which raised the salaries of congressmen and senators to $1,500 per session (roughly $31,250 in 2025 dollars). Supporters of the new law pointed out that congressional salaries had remained unchanged since 1789 and had not kept pace with the rising cost of living in Washington City.

The American people, however, had little sympathy for this argument. Outrage over what became known as the “Salary Grab Act” was swift and fierce, prompting almost immediate electoral consequences. Several state legislatures formally denounced the measure, and in the fall elections preceding the next session of Congress, two-thirds of the House of Representatives and half of the Senate were voted out of office.

Even members who had opposed the bill found themselves swept up in the storm, accused of benefiting from the same unpopular raise. The backlash transcended party lines—Federalists and Republicans alike faced the wrath of the voters.

Members of both houses soon repealed the Compensation Act, instead providing for eight dollars per day, and eight dollars for every twenty miles of travel from home to Washington. To the public, that seemed far more in keeping with the spirit of republican virtue.

What happened in 1816 was part of a wider historical arc. In 1789, the first Congress submitted a constitutional amendment to the state legislatures dealing with congressional salaries. It read: “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.” The amendment was not ratified at that time. In fact, it was not ratified until 1992, when it became the 27th amendment (the last amendment ratified as of November 2025). Since ratification, members of Congress have had to justify proposed pay raises to the American people—exactly as the disgruntled voters of 1816 would have wished.

Why It Matters

The “Salary Grab” of 1816 showed that Americans, even in the nation’s infancy, held deep suspicions of self-advancement in government. It also set an early precedent for the idea that public service should reflect humility and accountability—a theme that would echo throughout the 19th century and beyond.

Further Reading

C. Edward Skeen, 1816: America Rising (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003).

Christopher J. Leahy, President Without a Party: The Life of John Tyler (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020).

This post shares a story from early U.S. history for educational purposes. It is not related to current political events or commentary.