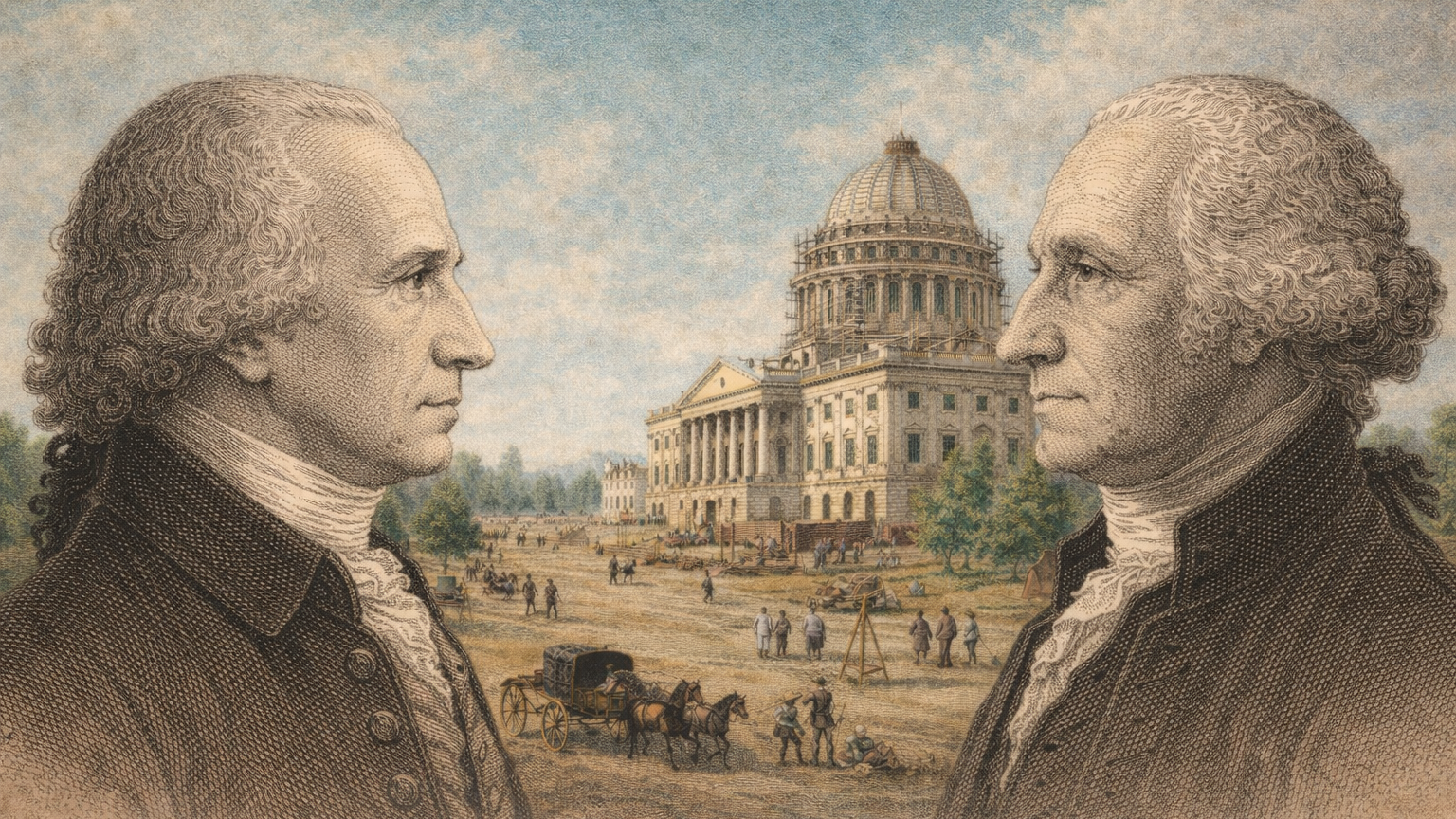

Washington and Madison: An Indispensable Collaboration

Collaboration was central to the formation of the American republic. The fifty-five delegates elected by their states to compose a constitution for the new nation in the summer of 1787 worked together—often contentiously—to hammer out the document that has served as the foundation of American government and law for more than two centuries.

Close collaboration also marked several of the founding era’s most consequential partnerships: the relationship between George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, and the intellectual alliance shared by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The now-famous June 1790 dinner at Jefferson’s home—bringing Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton together—helped clear the way for a political compromise that led to the selection of a permanent capital on the banks of the Potomac River.

Yet the most important collaboration in the development of that new capital has been largely overlooked: the partnership between Washington and Madison. In the words of historian Stuart Leibiger, it “remains the founding’s central team overall.”

Congress narrowly passed the Residence Act in July 1790, and President Washington signed the bill into law on July 16. His signature accomplished two critical objectives. It enabled southern congressmen to support Hamilton’s plan for the federal government to assume state debts, and it permanently fixed the nation’s capital on the Potomac.

Washington personally managed many of the details surrounding the creation of the new capital, but he relied heavily on Madison—then serving in Congress—for advice and guidance.

In August 1790, Madison drafted a detailed memorandum for the president that offered a broad interpretation of the Residence Act, particularly concerning the boundaries of the federal district. While acknowledging Congress’s stipulation that all public buildings be located on one bank of the Potomac, Madison argued that the ten-mile district itself could include land on both shores. As a result, the City of Washington was placed in Maryland, while the broader District of Columbia encompassed Alexandria, Virginia.

Washington again followed Madison’s counsel when negotiating with Potomac landowners whose property would form the new district. Madison advised that pitting landowners against one another would yield favorable terms for the federal government. Washington embraced the strategy with notable enthusiasm—at one point publicizing an exploratory trip up the Potomac as far as Williamsport, Maryland, to signal that alternative sites were under consideration. The maneuver worked, prompting landowners to offer more advantageous prices.

Madison also influenced Washington’s eventual decision to dismiss Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the brilliant but difficult architect charged with designing the capital. L’Enfant’s refusal to compromise and his combative temperament alarmed Washington, who feared that the project itself might be jeopardized.

Although partisan politics eventually drove Washington and Madison apart, for a crucial moment their collaboration shaped not only the physical development of the nation’s capital, but the future of the republic itself.

Why It Matters

The partnership between George Washington and James Madison reminds us that the American republic was built not only through debate, but through collaboration.

Washington brought authority, public trust, and a deep sense of national responsibility. Madison supplied constitutional expertise and legislative insight. Together, they transformed ideas about federal power into a functioning capital city—one rooted in compromise and long-term vision.

Although their relationship later fractured over politics, their early cooperation helped secure the physical and institutional foundations of the federal government. The capital on the Potomac stands as a lasting testament to what shared purpose can achieve in a nation’s most uncertain moments.

Source

Stuart Leibiger, Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999).