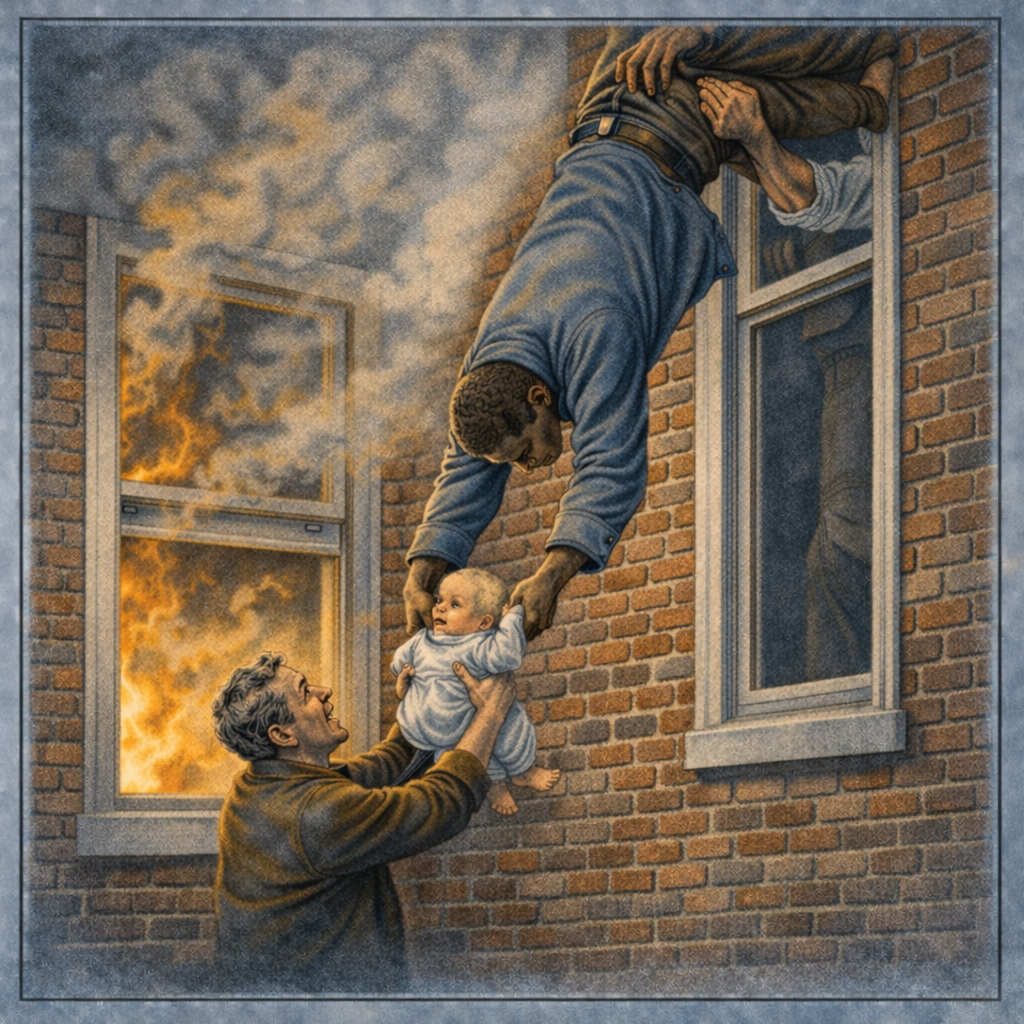

“Window to Window”: M. S. Anderson and the Early Morning Rescue of Six Children

A Morning Commute Interrupted by Flames

Just before dawn on March 21, 1900, a 21-year-old New Yorker named M. S. Anderson was walking to work along West 134th Street when something stopped him cold.

Smoke poured from a five-story brownstone at 185 West 134th Street. Flames were climbing fast—up stairwells, through wooden wainscoting, racing toward the roof.

And from a second-floor window, Anderson saw a father lean out desperately calling for help. Michael Nelson stood trapped with his wife and six young children, their only escape cut off by fire and smoke.

Anderson did not hesitate.

A Rescue Without Ropes, Nets, or Training

With two neighbors—J. J. Tucker and D. R. Thompson, who lived next door—Anderson raced into the adjacent building at 183 West 134th Street. The trio climbed one floor above the burning apartment.

Inside the apartment of Gottlieb Meyer, the three men devised a plan as dangerous as it was astonishing.

Tucker and Thompson gripped Anderson’s legs and feet. Like a trapeze artist, Anderson swung headfirst out the window with his body suspended in open air, swaying like a human pendulum.

Below him, Nelson lifted each child upward.

Anderson “managed to reach the children as they were held up to him by their father,” one paper reported, swinging them window to window, one by one, to safety.

Six times, Anderson reached out over the void.

Six times, a child crossed the gap.

Six lives were saved.

When the last child was pulled through, Anderson collapsed onto the floor—panting, shaking, utterly spent.

Firefighters Finish the Work

Fire companies soon arrived. Nelson and his wife were rescued by Hook and Ladder Company 23, under Captain Sullivan. Other families were led to safety by Engine Company 59, commanded by Captain Perley.

In all, eighteen people survived the blaze.

How Newspapers Remembered the Feat

Across the country, newspapers struggled to find language equal to what readers imagined:

One called it “a method of life saving novel to the Fire Department.”

Another described Anderson as “swinging from a window high in the air as a human pendulum.”

All agreed on one thing: this was bravery of the highest order.

Anderson was not a firefighter.

He carried no equipment.

He was simply a young man on his way to work who chose to act.

Why It Matters

Heroism does not always wear a uniform.

At the turn of the twentieth century, New York’s aged housing units were crowded, wooden, and often poorly maintained. Survival depended as much on neighbors as on official rescue.

M. S. Anderson reminds us that courage often arrives before authority—and that ordinary people, faced with extraordinary danger, can choose to become something more.

Image Citation

Illustrations:

Custom illustrations created for History in Two Voices using AI-assisted image generation, based on contemporary newspaper accounts of the March 21, 1900 fire rescue on West 134th Street, New York City.

Sources

Buffalo News, March 21, 1900

Brooklyn Times Union, March 21, 1900

Brooklyn Citizen, March 21, 1900

Democrat and Chronicle, March 22, 1900

New York Herald, March 22, 1900

If you enjoyed this story, you’re welcome to stay connected. Please complete the form below.

We share occasional stories from America’s past — no spam, just history.